Using Data to Inform End-To-End Iterative E-learning Design: 15-Minute Intro Course to DSLR Photography

THE TASK

As a passionate student of educational technology, I joined the cohort of 20 students in the METALS program at Carnegie Mellon University, where we pursued the most state-to-art theories and practices of learning design and engineering.

E-Learning Design Principles is one of the six core courses that go towards the METALS degree program. In this 12-week course, along with digesting a great amount of learning design principles regarding aligning learning goals, instructions, and assessments, I had the opportunity to lead an end-to-end e-learning design project individually, where I developed an e-learning module of my choice (photography!), continuously improved it, and tested it in an A/B experiment.

-

I’ve always been curious about photography. With advancements in camera technologies, photography and documenting through photos have become an accessible everyday practice in many people’s lives.

By taking photos that record a moment to its full potential, or tell a story that you want to be understood, some skills are making a difference. Although cameras in our phones are decent enough, learning how to use a DSLR in manual mode is helpful in circumstances where phone cameras reach their limit (regarding their flexibility and capability).

THE PROCESS: OVERVIEW

🔍 DISCOVER

Needs finding from learners, theories, and experts-

There are many things to document and align before jumping into designing the course. I needed to build learner profiles: who are they, what do they want to learn and what do they need to take the class

To answer these questions, I conducted five 1:1 in-depth interviews with my targeted learners (adults, non-DSLR-camera users, interested in photography) to understand their learning goals.

-

Set goals for the course — good learning design set clear, actionable, and measurable goals at the conceptual, skill, and dispositional levels.

With my (limited) amount of photography skills, I started by choosing this one task that the learners of this course should be able to complete after taking the course: taking a photo of a child on a swing. I mapped out a flow chart explaining what a photographer might do in different scenarios (e.g., when the environment is bright, or when there are multiple people standing in the background).

-

You may think that if someone is an expert in something, they can just reflect on what they know, right? Unfortunately, learning theories indicate that intuitions about knowledge (even one’s own knowledge) and learning, are often wrong! One needs data to provide models and new insights — collecting data and interpreting it helps create knowledge goals.

In any subject matter area, there is implicit knowledge that even experts in the field will easily overlook (“expert blindness"). As an instructional designer, my goal is not to become an expert in photography, but to work with photographers to uncover that knowledge that paves the foundation of good instructions for my students.

In my case, I need to collect data on how experts solve this very task (“taking a photo of a child on a swing”). One appropriate method to help collect good data is expert think-aloud, where I give them a task and ask them to share their thought process. In an in-depth interview format where I talked to them 1:1, I was also able to follow up with anything in the moment.

I recruited 5 experts in photography instructors (photography instructors, n=2; photography practitioners, n=3). I recruited 5 experts in photography instructors (photography instructors, n=2; photography practitioners, n=3).

Think-alouds of photography task with photography practitioners (n=5)

From the five conversations, I was surprised by how “unstructured” and dynamic a photography task could be. Different photographers take different approaches, which will show differently if the data were put in a CTA model.

I was informed that the cognitive model of my designed task was too complicated for a novice user of a DSLR camera. As a result, I would need to break the model down into several chunks to guide my assessment. I decided to focus more on conceptual skills and procedural skills for my target learners (beginners in using DSLR cameras).

Contextual inquiry with photography instructors (n=2)

I also decided to also conduct contextual inquiry sessions with the photographer instructors to understand their work environment, which could provide important insights into the specific subject matter area.

Interview main objectives:

How they assess others’ photography skills

What they think is important in a photography course

Their teaching goals

General challenges of learning photography

Main takeaways during discover phasePrinciples of my instructional content:

Keep the instructions simple

Use a lot of images and videos

Should help students understand that DSLR cameras can “tell a story you want it to be told.”

Main topics to teach in this intro course:

ISO

Depth of field

Shuttle speed

Aperture

🪡 DESIGN

Then it comes to designing the instructions and assessment of the course content!

>> DEMOAmong all the design principles, I wanted to make sure that the following ones were integrated based on my understanding of the subject matter area.

>> DESIGN PRINCIPLES-

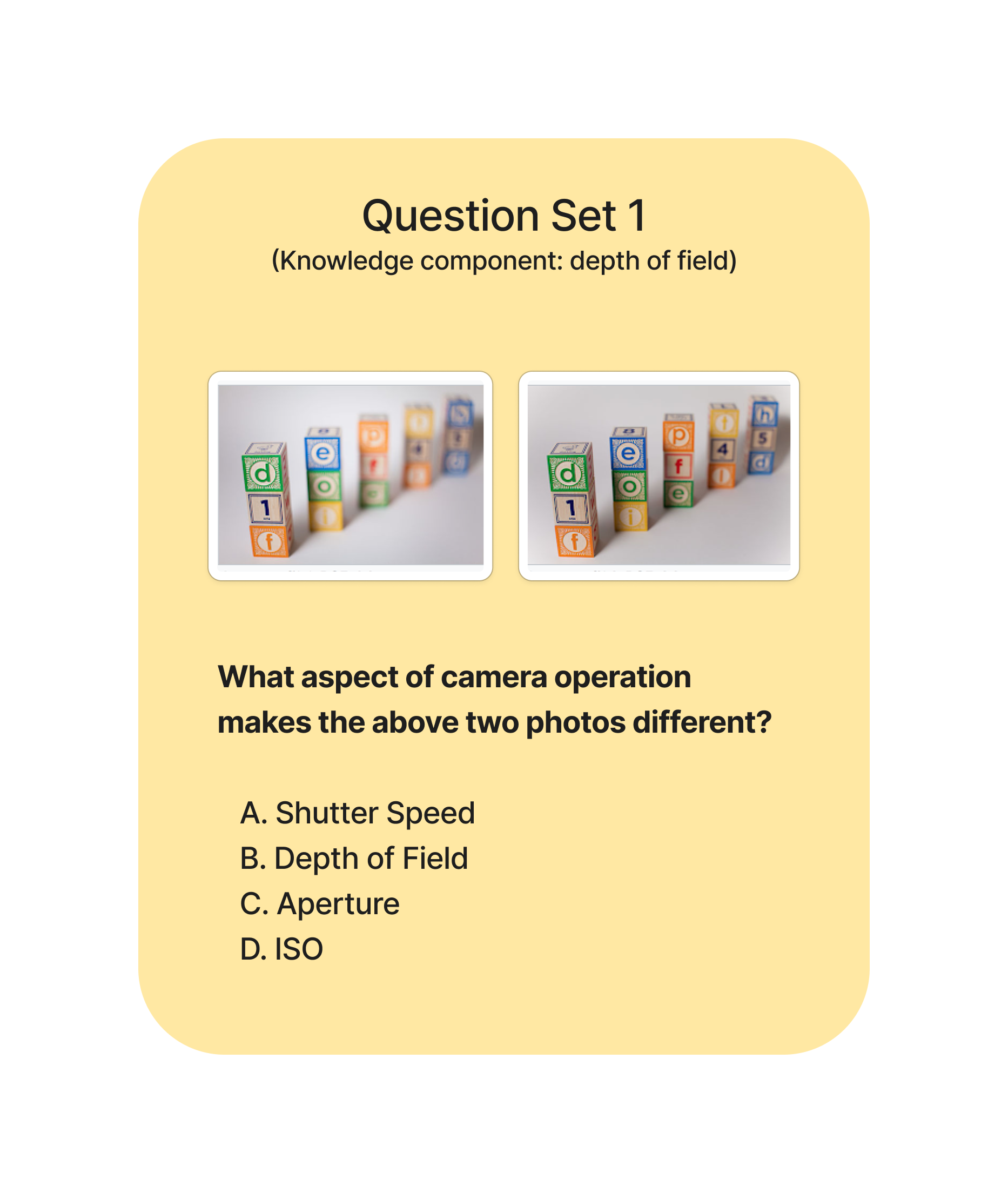

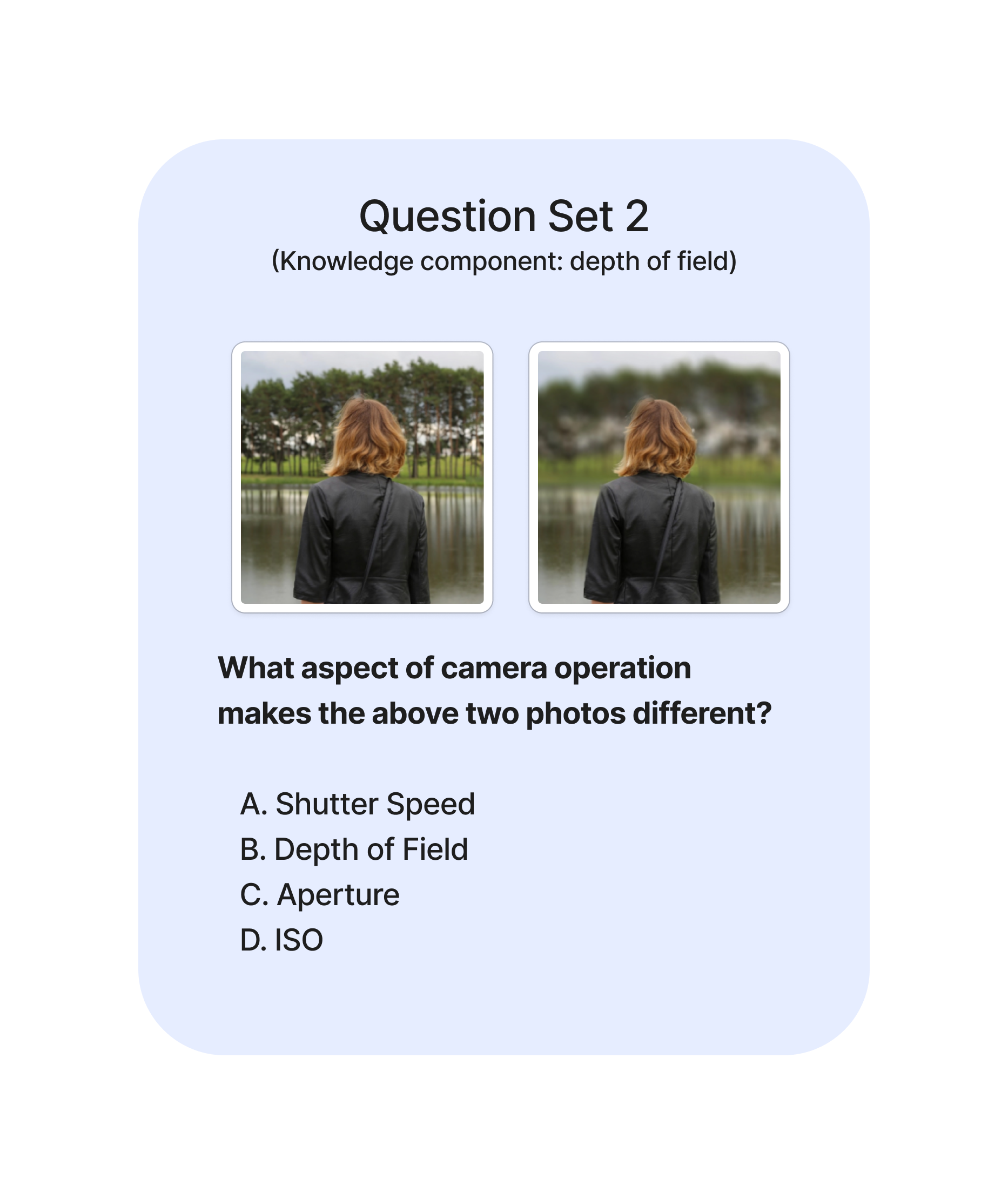

Based on theories in cognitive science, using contrasting cases helps learners catch the key differences between two photos, and guide them to think about what might have caused the difference.

-

During the Cognitive Task Analysis sessions (CTAs) with photography experts, they reflected that they think videos are really helpful for online photography instructions. I am also including a video for the last part of my instruction, “panning a moving object.”

-

Since people can actively process only a few pieces of information in each channel at one time (Limited Capacity). For taking a photo with a cell phone and a DSLR (in manual mode), the cognitive load is on two different levels. For a novice in using DSLR cameras, thinking about multiple operations (ISO, shutter speed, and aperture) simultaneously is challenging. I plan to segment these concepts into chunks before exposing learners to thinking about these concepts together.

-

Learning occurs when people engage in appropriate cognitive processing during learning, such as attending to relevant material, organizing the material into a coherent structure, and integrating it with what they already know (Active Processing) This course, as an intro to a lot of conceptual knowledge in DSLR, is not offering students opportunities to practice hands-on photography. As a result, it is an important question to think about how to motivate learners to find relevance in the course to field practices.

>> FLOWAssessment is an indispensable part of learning design. To test the effectiveness of course instructions (so that we can answer the question “has the student really learned something from spending time on the course?”), a good practice is to embed a pre-test before the instructions (the lesson itself) and a post-test after the instruction portion. The pre-test and post-test should be targeting the same knowledge components (so that it’s testing the same things) but should be different questions (so that learners shouldn’t be performing better in the post-test just because they remembered the answers from the pre-test.

Each learner will go through three parts of content in this course:

Pre-test

Instruction with practices

Post-test

Below are a few pairs of examples of how two questions can target the same knowledge component (KC) without being the same question:

>> TOOLINGI wanted the course experience to be:

interactive

mobile-friendly

multimedia-friendly

supporting branching and data collection

I decided that the survey platform, Qualtrics would be great for this! It was also a great plus that it was a user-friendly tool from my perspective.

🛫 TEST

Experiment design to compare two different types of instructions

As course designers, we were also challenged to create different versions of instructions and find out if one form of instruction would work better in teaching the same knowledge points. I was curious: is it more effective — during the instructions — when the practice questions come with hints or are hints bad for learners? I designed two sets of instructions, one with hints and one without hints.

To test which version of the instruction worked better, I set up an experiment, where each learner would be placed into one of the two versions of instructions. To find out the effectiveness of the instructions, as an instructional designer, I’d compare the learners’ performances in each group with their post-test scores versus their pre-test scores.

Course flow: experiment design grouping

Pilot testing with real learners

I decided to launch this course to a small group of learners to understand if any blockers existed. You could think of it as a “usability test” of a learning experience. However, the main difference between learner experience testing and user experience testing is that “learning” is supposed to bring challenges. Not the tricky-question type of challenge, but learning is not only about completing tasks, but also the performance.

After having four learner participants complete the course (pre-test + instructions + post-test), I decided to iterate the course in the following ways:

Provide context to learners so that they are not overwhelmed by the pre-test.

“The pre-quiz is way too hard for me. I am not the right person for the lesson, right?”

I decided to apply the Personification Principle to guide the learners that the pre-quiz being “too hard for them” does not mean that the lesson is not at the right level for them, but to test their current knowledge of the lesson.

Clarify questions with less ambiguity so that the test is only about assessing knowledge.

“In the Question, ‘as the aperture becomes smaller,’ does it mean the number (‘F-Stop’ / ‘F-number’) the indicates aperture is smaller, or the aperture part of the camera is more closed-up?”

This was a great question that needs clarification. Two different kinds of understanding (both correct) would give two opposite answers. And if I had not received this piece of feedback, I would assume that people who answered this question wrong were because they did not understand the concept, not because my question was misleading. Considering that A is still the only correct answer, I needed to rephrase this question to make it more clear: “As the camera’s aperture closes up.”

👩🏻🔬 ANALYZE

A/B test/experiment findings

I sent the course to friends and family, inviting those who are interested in DSLR camera photography but aren’t proficient in using one to take the course. Very fortunately, I collected 67 fully completed lesson data points!

This set of analyses imply that pre-test set 1 and pre-test set 2 are at similar difficulty level, which aligns with the design attention.

This set of analyses imply that instruction B (with hints) are better than instruction A (without hints) in terms of helping learners perform better in assessments.

Areas of improvement

Although I learned from the A/B test data that the two question sets are at the same difficulty level and that the score improvement was due to the instructions, once I looked closer into the data, I noticed that there was one set of questions (targeting the same Knowledge Component) that showed significantly different scores among learners’ performance. It is an opportunity to investigate why this happened, and potentially switch out images to make sure that questions that target the same knowledge component in pre-test and post-test are at the same difficulty level.

💭 FINALLY, SOME REFLECTION…

“Yulin is innovative in creating a module that is simple, and she manages to avoid overwhelming learners.” First of all, I was really glad that 60+ learners completed the course.

I found the scoping and goal-setting part of the course the most challenging. I started with a lot of things I wanted to include in the instruction, but focusing on clear goals that are the appropriate level for learners is so important for later efforts in aligning assessment and instructions. Again, as an instructional designer, I better continue to practice using data (sometimes qualitative, other times quantitative) to inform every step of the design process: it’s not the goal to become a subject matter expert in the area being taught, but an effective thinker, communicator, and developer of the learning experience.