Teaching English to Kids in the Family with Duolingo: Tips and Thoughts

Disclaimer: I don’t work at Duolingo. I did not get paid to write this article. I welcome any discussions.

Three months ago, my mom, currently living in China, gently asked me on a phone call, regarding whether I’d be ok with spending some time with my niece and cousin and tutor them English.

“Of course, of course!” I told my mom, “you don’t have to convince me any further.”

I always enjoy the task of teaching English, and having studied applied linguistics at grad school gives me even more confidence to say: I not only am interested in it but also know what I am doing. Well, I do sometimes go back and review my “teaching philosophy” that I wrote for one of the courses I was taking.

So, how did I get started with the lessons with them? To gain more understanding of their own proficiency levels, I decided to tutor them individually as a start.

Thea is my niece, currently in 3rd grade and just started to learn English. Cooper is my cousin, currently in 5th grade, and has studied English at school for about two years.

🙋🏻♀️ WHY DUOLINGO?

Handy materials

Pulling my knowledge and experience in language teaching, I know it’s important to have teaching materials like a textbook, handouts, and exercises to structure my lessons around — “free chatting” does not work well in most circumstances: for beginner learners, producing the language will not take place if students do not have access to structured language content as a tool to generate their own sentences.

“i+1” content

Also, to make the lessons are appropriate for my students and their current proficiency levels — using linguistics terms, the content needs to be at “i+1,” where learners can reach with some efforts (not too difficult, and not too simple). Duolingo, based on my understanding, lays out content and practice in a structured roadmap, which makes sure that content is advancing step by step.

After-class independent use

To make sure that my students still have opportunities to learn and practice, it’d be great if my students could use the tool/platform on their own when I am not around — it’s much more sustainable for their future learning.

To meet these needs, I decided that Duolingo would be a great resource for me as a teacher — handy materials, “i+1” content for my students, and the flexibility for students to use on their own outside of my classes (with a dashboard to monitor!). I was also surprised to find a web version of the app, which makes it so much easier for me to screen-share in a meeting while I am on my laptop!

My Spanish learning dashboard; the English courses will be in Chinese for my Chinese students

🎉 Another key reason: Duolingo Stories

As most of you might already know, the Duolingo lessons are mostly based on the translation method: a type of language learning practice based on translating between the target language (the language the learner is learning) and their native language. It is often a debatable method that emphasizes the constant change of perspectives between languages, rather than providing the immersion of a language (like how a person picks up their first language). The translation method has its good and bad, which I can easily discuss my way into a term paper and will ask myself to save us from this discussion in this article.

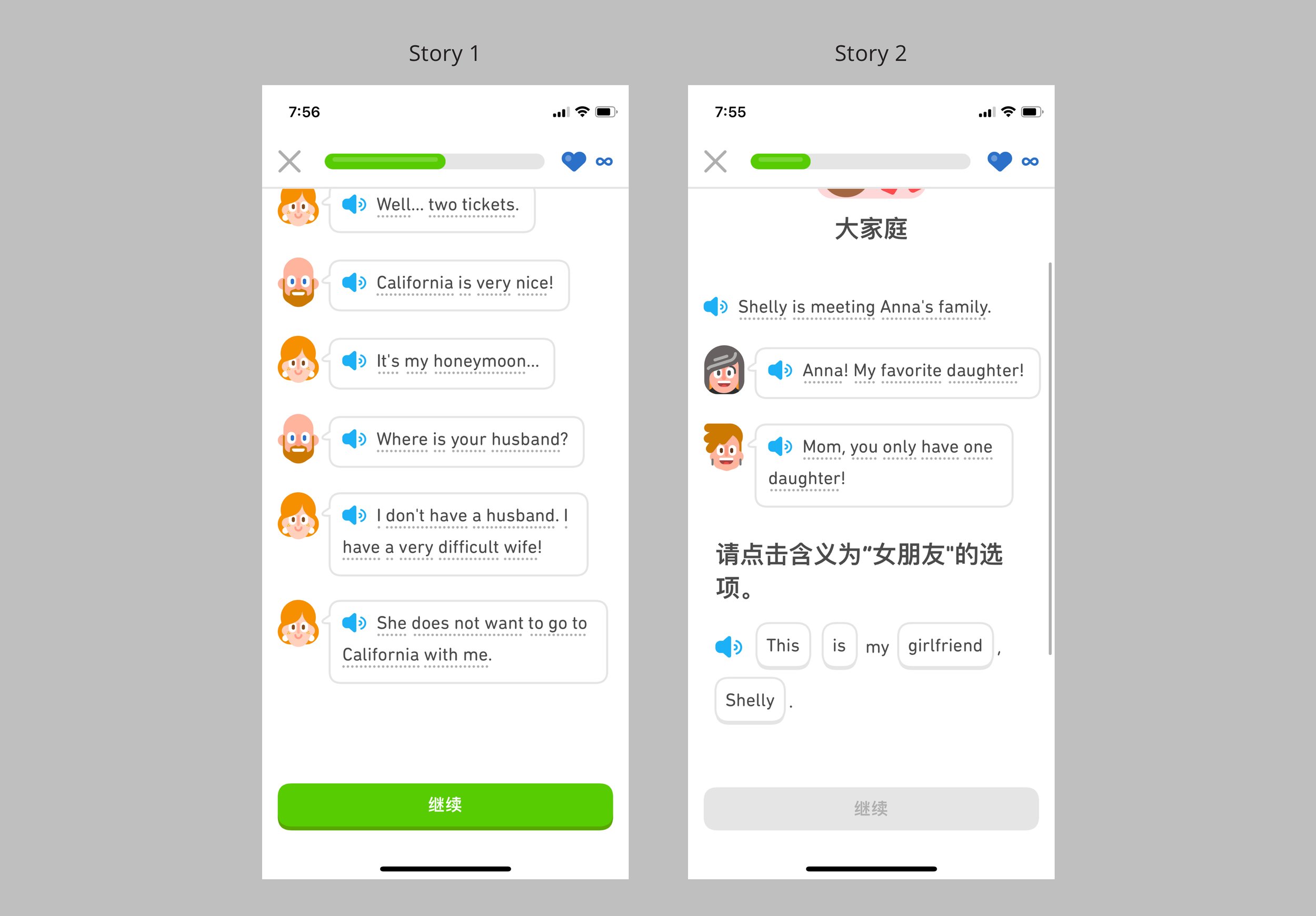

The coming of Stories, surprisingly, completely shifted that argument by offering learners an authentic dialogue environment without the translation practice. The content and design also makes sure that users are still able to look up words and respond to comprehension questions, asked in their native language to check their understanding.

The greatest thing about the Stories is that in each story, there is an interesting conversation narrated by 2–3 characters, sometimes plus a narrator to describe the context. The audio quality is amazing and seamless and the tone is articulate while full of drama (imagine real actors playing out a scene). It’s witty and full of life. For my learners who have little access to authentic texts and listening materials — let alone the dramatic and diverse tones. I believed that these well-played-out dialogues would bring a new world to my young learner students.

New update: now the Stories come in three levels: Reading, Listening, and Speaking, where before there was only the Reading level. In my video lessons with my students, we focus on the Reading levels because as a live teacher, I can use Reading to do all kinds of interactions with the students; students can make use of the Listening and Speaking sections on their own.

👩🏻🏫 HOW I USE DUOLINGO IN MY LESSONS

1. Integrate corrective feedback and targeted practice — especially on pronunciation

In my lessons when I have face time with my student, I want to take the opportunity to provide instant feedback as much as possible. When I had my first lessons with Thea and Cooper separately, I was surprised to find that both of them pronounced “brother” as /ˈbrəLər/ (instead of /ˈbrəðər/) — same went for “mother,” which they pronounced as “/ˈməLer/.” My assumption of the source of the issue is (1) their teachers’ accent (both of them are learning in approximate small cities in China, where teachers are more local and probably speak a shared dialect and with an accent), and (2) the teachers don’t have the ability and/or opportunity to correct their students’ speaking.

In cases like this, I pull out a Google Doc (during my screen-sharing) and highlight the minimal-pair pronunciation practices for them. I have also introduced them to IPA, which they both reported to be “really overwhelming” based on their interaction with their respective private tutoring school their parents sent them to. Now, having worked with me for a while, I am glad that they have started to request that I spell out the IPA for them to practice.

In the following two weeks, I kept prompting them to re-pronounce the “th” sounds whenever I’d hear an inaccurate pronunciation. (Currently, I am happy to report that they have been consistently pronouncing this sound correctly!)

Besides pronunciation practice, I also expand on the sentence exercises in Duolingo and ask my students real-life questions for them to respond to.

Expand on content

2. Read aloud, discuss, and role-play it out

Besides all the great things I shared about Stories earlier, I want to explain a little more about how I use them with my student. The main structure is that we go over the short story together by having the student listen to each sentence and read-aloud after it, and then we discuss things they have questions about around vocab, sentence structure (grammar points), and sometimes pragmatics (“what do they mean by asking this here?”). And finally, we role-play it out.

To make sure that my student gets to experience the seamless interactions Stories bring to the table, I sometimes invite them to share their screen with me so that they could be in control (more to be shared in next section). I am really excited by how they are able to imitate the dramatic tone of the narrators who play the characters. And more importantly, they really have fun doing it.

The reason why I complete Stories with them was that Cooper specifically asked for it.

“I don’t understand the stories when I do it on my own,” he said.

I was surprised when I first learned it but also glad that he told me this. I realized that the Stories had a lot of social pragmatics that these kids had never accessed — it was really unfamiliar to them. For example, he had questions about why the shop assistant was asking the customer “why does he ask for a receipt.” Another time he asked me why people say “thanks, bye” in English (there is no natural correspondence in the Chinese context). I am glad my time with him allowed him to ask questions like this freely — it is more than “understanding the words and the sentence structure,” it really comes to using the language in a context.

3. Take turns to screen-share between teacher and learner

In my class, I log in to the web version of Duolingo and screen-share with my student. I can play the content for them, ask them to repeat, and ask questions in between to check their understanding.

In another half of my class time, I ask my students to screen-share their Duolingo app screen with me. This way, they get to experience the interactions Duolingo has to offer. The challenge is that sometimes they tend to click through things fast, so I had to interrupt them to correct their pronunciation, remind them to read aloud, or ask them questions.

I share my screen vs. my student shares their screen

💪 WHAT REALLY CHALLENGES ME

This “teaching pride” does not serve me without challenges.

The content and stories in Duolingo, let me see how I should put it — is progressive. As a user and language learner of Spanish, when I was using Duolingo, I was thrilled to see some progressive content in the app, such as same-sex characters who are couples in the story narratives. I was thrilled. However, when I became the teacher who used the same content to teach learners, I had to think more layers — I am not saying it’s a bad thing, at all.

A learner of a language should not be taken away from the context of the language in question. (Like how the movie Bohemian Rhapsody was shown in movie theatres in China, all Freddie storylines of his gay relationship were cut — I never want to justify that.) When my niece and cousin were reading the stories that included content about same-sex relationships, I wanted to be prepared about what they’d ask and how I could respond.

“Progressive” content

They did ask about it, and I said: “yes —in the US and some other places — it’s ok for two women to get married; the same goes for men (and others).” “That’s not allowed here,” Thea said.

“Yeah, I know what you mean,” I said, hoping that they wouldn’t get bullied for distributing this piece of information to their peers or teachers at school. I can’t say I am not proud of this exchange.

I know that many are challenging why learning language has to do with “being progressive.” My question to myself is: can I make sure to balance both contexts and make sure to treat my young students with respect? These are stories of real people and real lives, being seen. If that’s not the goal of learning languages, I don’t know why I am doing what I am doing.

To that, I have a lot of respect for the content Duolingo is creating. What I want to add is the support that the platform should provide learners and teachers with on the cultural and pragmatics levels.

🛸 APPENDIX

1-Using video conferencing technology

I also want to share some tips on the conferencing tools and devices I am using. Since Zoom has been blocked in China, I explored a few other tools — MS Teams being one that works. Later I also explore Tencent Meeting (a copycat of Zoom that grew big in China) when my niece’s MS Teams stopped connecting even after installing updates.

My niece (we’ll call her Thea) has an iPad; my cousin (Cooper) has a Huawei tablet. Depending on the different devices they use, meeting tools like MS Teams and Tencent Meeting come with pros and cons. Below is a log where I document technical difficulties.

2-Areas I wish could be improved

Unlocking content: As an “English teacher user” of Duolingo, I wish there was a way for me to “unlock” all the English lessons and Stories in the app. Currently, the web version of my teacher account allows me to jump to specific topics for class use without having to unlock every part as a learner does, but the practice is not as abundant as the learner end, and Stories are not accessible here. As a result, I’d have to “power through” a lot of content before class so that I can access more content freely in class.

Keyboard use: There are some questions that ask users to type in their answers in the target language — I used to frown upon them, thinking they were boring exercises that did not aim for students' everyday language skills. However, as I worked more with the kids in China, I see how much they struggle with this question type. There could be two reasons: (1) they lack practice in spelling and writing; and (2) surprisingly, they rarely have the opportunity to type on a keyboard, and they are unfamiliar with the keyboard. With parents and schools trying to limit their screen time in light of the prevailing use of digital devices, young learners are not encouraged to use the laptop as much as I expected. (Based on my work and research on parents in China, I also learned how they perceived typing with a keyboard as “offering too many hints in spelling and bad for their spelling skills, compared to handwriting.) Also, as more touch screens are being used, they sometimes resort to the handwriting-recognition function, which is unfortunately much slower than typing with keyboards. I was wondering if there is any room for Duolingo to come up with any keyboard-practice-related activities.